Jetze Plat — a level playing field

"It was an unlucky — no, crazy — period to change a rule, just before the Paralympics in Paris, and it affected my preparation in a big way."

A rule change is easier to accept when it impacts everyone — the camaraderie of a shared inconvenience. But in a sport where equipment disparity is already a performance and big-race determinant, it's hard not to feel a sense of injustice when amendments can be so specific that a new standard is only relevant for one competitor. 6 months out from the Paralympics, Jetze Plat went back to the drawing board.

There is nothing off-the-shelf in Para triathlon or wheelchair marathon racing — everything is uniquely modeled around the body of the athlete. "It takes years of testing and development. I'm always interested in that side of the sport so I enjoy testing new things, but it costs a lot of time. You always have to find the balance between focusing on training and at other times focusing on improving the equipment."

Jetze was born with missing bones and no knee in his right leg and a short left leg. In 2008 his right lower leg and foot were amputated. The unique shape of his hips and legs require a development process that takes years to refine — discomfort being the enemy of speed and power.

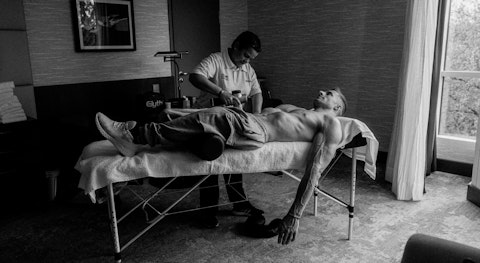

"An hour and a half in this position is quite stressful for the body, so it's always a combination of the power output, the aerodynamics, and being able to sit or lay down comfortably."

As reigning Paralympic champion in Para triathlon and handcycling, everything was building towards a new crescendo in Paris. A chance for friends and family to see him race on the biggest stage. "For the last five years we were building my performance in this position, and then 6 months before the games they made the decision to change the rules."

"It was really shit. Normally the focus is 100% on training and now we had to spend a lot of time creating a whole new position and rebuild the racing chair. So it was not really positive."

All the work on being comfortable and efficient with the equipment needs to be signed off a long way from a major race, allowing the athlete time to prepare physically and mentally. This didn't feel like a simple setback — it had the potential to derail the entire process. "Because of how my legs are, I sit on my knees with my legs out the back of the chair. I was the only one sitting in this position, so I was the only one affected by this rule change. My only option was to see if I could sit slightly differently."

It seems innocuous — just move a bit in order to comply with the new rules. But that is undoing years of being in the same position, of the body feeling at one with the equipment. To move the body and machine forward efficiently requires a balanced interplay between the muscles in the arms, shoulders, core, and back. Then consider how the angle of the lean either opens or closes the lungs — being flatter may give an aerodynamic advantage but it also restricts the expansion of the chest. And all of this is again centered around comfort. A body that doesn't feel supported — or worse, hurts — in the chair will not be able to catch the stroke. When it's right, timing should appear effortless — the body and the equipment in harmony. Jetze can sense feedback from the road — the subtle sensations that become second nature and enable him to maintain momentum.

Jetze acknowledges that he can lean on the Dutch federation for help, and that other athletes don't have the same depth of support to fall back on. "We have quite good facilities, especially on the equipment side, but there are many countries that don't have the same opportunities to test, or even buy a handbike or a wheelchair." As the sport grows, so does the gap in accessibility to the best equipment. The result is a double-edged sword that's only getting sharper.

"Sometimes it's really positive — people want to see top sports and the highest level of innovations — but at the other end you try to make a level playing field and that gap is a little out of context now."

It’s an uncomfortable paradox for a sporting arena that embraces inclusivity. For athletes starting out, the barriers — particularly cost — are significant. The race to be the fastest and the rapid advancement of innovations at the front of the sport has not created a slipstream for others to follow behind. Individual projects and big investments write exciting headlines, but it's not lifting the whole sport evenly. It's something that Jetze is aware of. "We all like to develop the sport, but the group who have the money, the people, and the companies around them is quite small."

In a fast-moving sport experience is also a valued commodity. With four Paralympic Games (7 gold medals) and seven Para triathlon world titles, Jetze is in a position to let the years of development know-how and race-craft filter through to the next generation.

"In the end it's really cool to show what we are doing and what is possible. The main focus is on winning gold medals, but for me it's just as important that we also focus on inspiring and letting people see what we are doing."

Twenty years of racing requires a moment to reflect on how the sport is taking its toll on the body, and there comes a tipping point where the focus shifts from racing in the sport to developing the sport. "Next year will be all about marathon racing, but after that, I don't know — you'll have the ask my shoulders. For sure I will always stay involved in the sport and help the new talents. I have a lot of experience about the life of an athlete and everything around that, so I hope to help the global development of the sport." It's about redirecting the passion towards helping raise the level of the sport across the whole scene — not just at the front.

Although there is still a lot of work to be done for his wheelchair to be where he wants it for marathon racing, in Paris, Jetze’s won gold in the Para triathlon, Road Race H4, and the Road Time Trial H4.

Words by Ross Lovell, Stills by Jojo Harper