Vernon Norwood — rise from nothing

“By the time we could go back, it was a disaster. A terrible disaster” — Vernon Norwood, Olympic 400m runner

There’s a discomfort that rises when trying to suggest, on some level, that Hurricane Katrina was a moment of luck. For many, all was lost — homes, communities, lives. As Katrina entered the Gulf of Mexico, intensified, and set itself on a new course, so it also determined a new course for the lives of the people in its path. For Vernon Norwood, no community remained. His life in New Orleans was over.

There’s a discomfort that rises when trying to suggest, on some level, that Hurricane Katrina was a moment of luck. For many, all was lost — homes, communities, lives. As Katrina entered the Gulf of Mexico, intensified, and set itself on a new course, so it also determined a new course for the lives of the people in its path. For Vernon Norwood, no community remained. His life in New Orleans was over.

“It was just real rough, you know. Probably one of the most notorious neighbourhoods in the US at that time, not just in Louisiana. But we made the most of what we had.”

It was rough, but it was home. Regardless of circumstances, being displaced from everything you know will always create trauma. “I didn't bring anything with me. And I didn't really want any of that stuff anyway 'cause all that stuff could be replaced. The only thing I just, you know, was upset about was pictures. A lot of those memories that I had as a kid, with my brothers and my mom. A lot of those pictures are gone — we don't have those.” The realisation of good fortune can only come after a period of reflection — once it was possible to see how far he’d come. For a while there was anger and Vernon admits that it took time to appreciate how hard his mother worked. How they had always talked about leaving New Orleans but moving need resources and, often, money. In the end it was a natural disaster that paved the way for a new future.

We’re chatting in Vernon’s lounge and he’s apologetic for the temporarily minimalist setting. “I’m getting the floors done, so all my furniture has been shipped out for a while.” It’s a modest place. A quiet, pleasant residential area a few miles out from Baton Rouge. Rows of New Balance trainers are the predominant feature. Perhaps there’s a preconception that a gold medal means immediate promotion to a lavish lifestyle. Vernon is refreshingly grounded. There are suggestions of his achievements — athlete passes to the biggest events, a framed photo, and, tucked behind the sofa, a set of recovery compression boots. Everything else is reassuringly normal. Including Chloe, his dog.

There’s an obvious question. If Hurricane Katrina didn’t happen, where would he be?

“I don’t know. I really don’t know. The friends that I hung out with are now either in jail or they passed away, or they're just not doing anything... I think my mother is blessed to see that she has all four of her boys breathing. It is a blessing, especially coming from where we came from.”

Vernon’s roots are in New Orleans, but his life events have changed him — the boy who grew up running and having fun in the streets is now almost unrecognisable. “I have to speak differently. I have to talk differently. Like now, I speak more clearly and better than I used to. People are, ‘Oh, you're from New Orleans? You don't sound like that’, you know.” And while the plush, wealthy setting of LSU, with its lakeside grandeur and huge stadium, is in some ways the demographic antipode to the neighbourhood in which he grew up, there’s no doubt that the muscle memory of his childhood remains. “Certain things now, you know, I speak when I'm spoken to or, just always nice, respectful, and kind to people. And it was something that I’ve always had. If someone speaks to you, speak back. Someone holds the door for you, “Thank you. No, Sir. Yes, ma'am”. You know, that's the laws that I was raised under by my mother. Be respectful to people because respect, it goes a long way”

You can’t unlearn — or unsee — the experiences of growing up in that sort of place.

“I've seen all of those things that people rap about. They say all that stuff and I'm like, yeah, I’ve witnessed all that. You wouldn't believe half of the things I've seen, but I don't say or speak too much about that because it humbles me to see that I will never be in those situations ever again.”

When you grow up in a place of real crime and real violence you can’t be blind to those acts. It’s an exposure that’s almost exclusively unrelatable. Something most of us think we know because of glamorized movie plots. It doesn’t elevate Vernon to talk about it publicly. He doesn’t try to claim any bragging rights. He rises because of an understanding of the realness of having been in that situation and uses that experience on a personal level — it’s his story to use.

“I know what it's like to be in rough areas and be in rough spots. You know, we are all human. We're going to have moments that's going to challenge us tremendously, and it'll make us uncomfortable. But it's up to you how you channel your energy and channel your thoughts. How to manoeuvre into the best spots for you — how to utilize your strengths.”

Spend time with Vernon and his positivity becomes infectious. It’s easy to envision him in a mentor role — as someone who has transitioned from social extremes he has life values and knowledge worth listening to. There’s a hunger to share that experience and to help others.

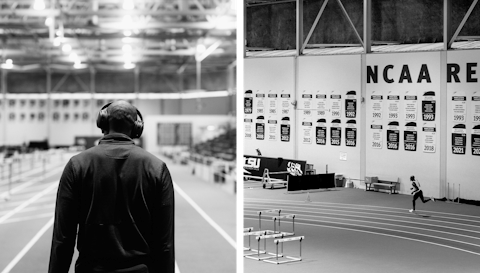

For now, Vernon keeps lapping the track. There’s still a desire to progress as an athlete — he’s not done yet. But when the time comes to pass the finish line for the last time, there’s no doubt that his influence, his charisma, his dogged attitude will help others rise too. A rising tide lifts all ships.

Words by Ross Lovell, Stills by Tyler McCain